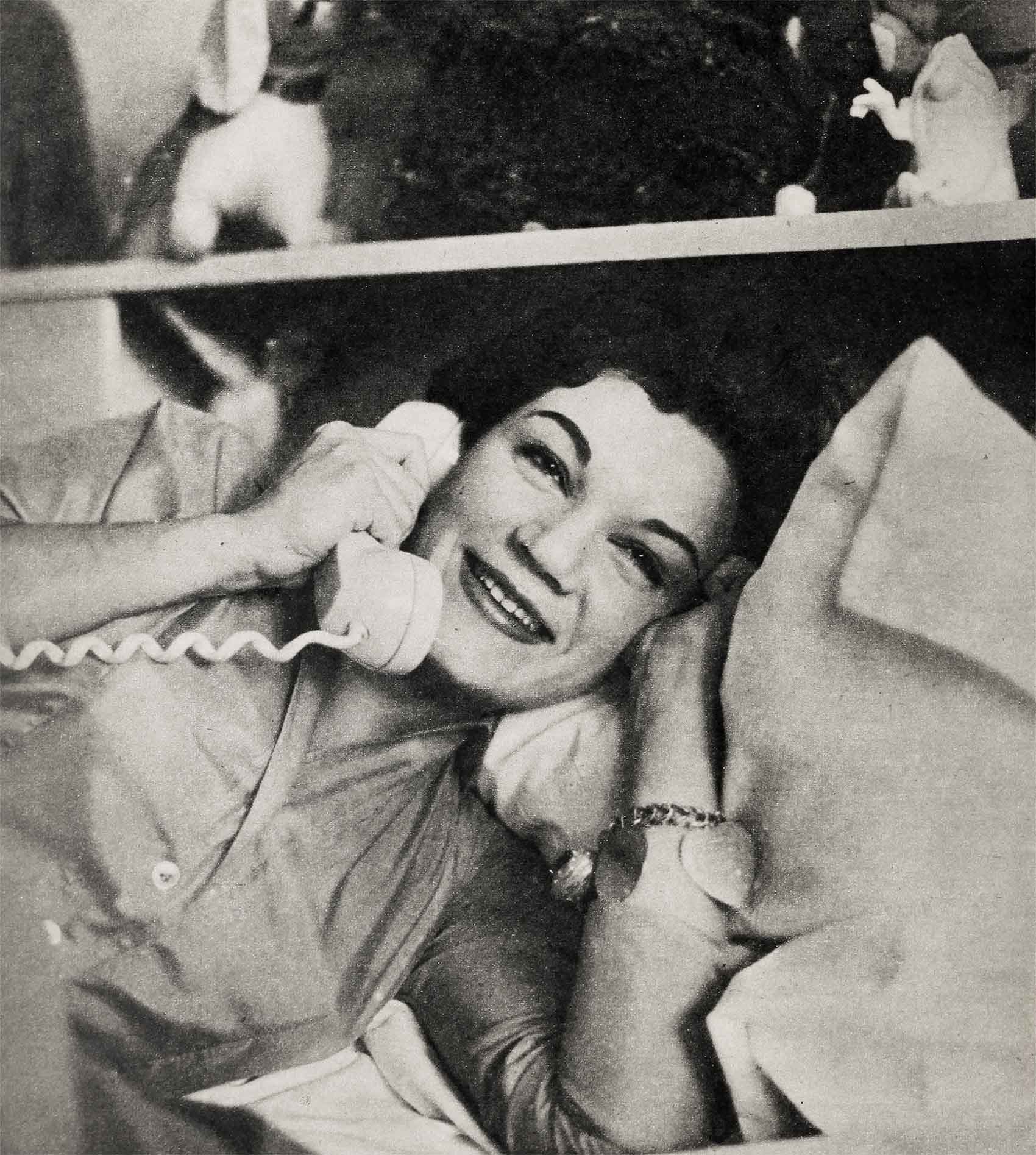

She Carries Spring With Her—Connie Francis

She’s the girl who inspired composer and singer Neil Sedaka’s first hit record, “The Diary.”

She’s the girl who believe in Bobby Darin in the pre-“Splish-splash” days when she had to lend him seventy cents bus fare to get back to Jersey from Times Square.

She’s the girl on whom a substantial number of today’s glamour boy recording stars have a crush. In fact, one of them said, “It isn’t just that she’s beautiful and fun and a fine entertainer. She’s such a . . .” He searched for the word and came up with an old-fashioned one. “She’s such a good girl.”

She is also the only new girl singer to break through the all-male dominance of the rock ’n’ roll revolution to score with three gold records and a succession of hits.

Her name: Connie Francis. Born December 12, 1938, in Newark, New Jersey. Daughter of Ida and George Franconero. Father is a roofing contractor and an amateur musician. Brother George, Jr., is in college. Lives in Bloomfield, New Jersey.

Her titles: “Most Promising Female Vocalist” in The Billboard’s disc jockey poll. “Best Female Vocalist of 1958” in The Cash Box vote. To make it international, Patrick Doncaster, one of Britain’s most influential record critics, named her “New Girl of the Year” and wrote in The London Daily Mirror, “American youngster Connie Francis takes old songs off the shelf, dusts them down and sings them like an angel.”

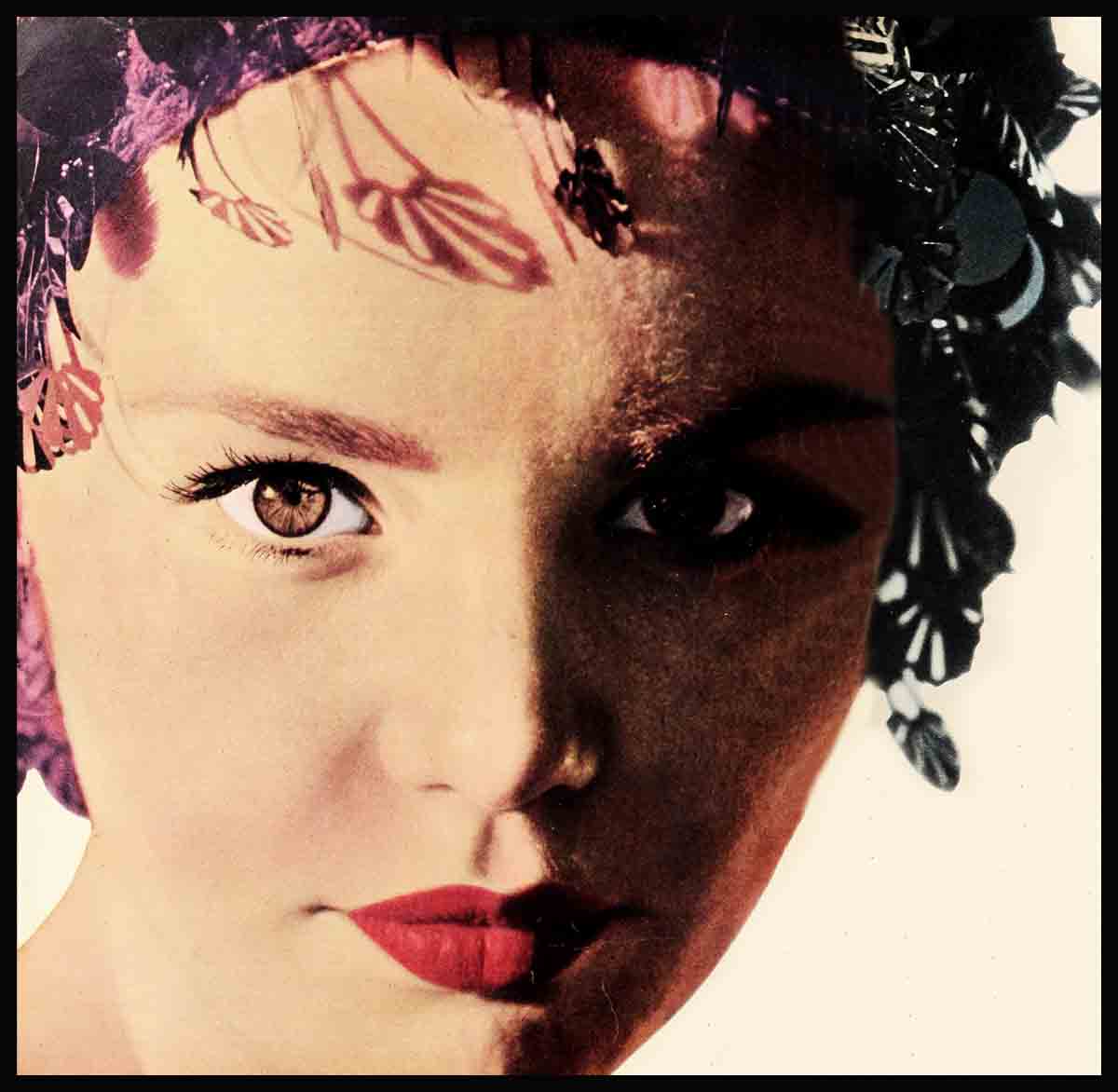

This new queen of popular song is a doll-faced, doll-sized charmer who delights both her dressmaker and wolf-whistling males. She’s five feet, one and one-half inches tall. “Don’t forget that half-inch,” she cautions. “I try to stand tall.”

Ask her her measurements and she replies with a twinkle, “Bust, 34½—when I take a deep breath. Waist, 22—before dinner. Hips, 35½—and that’s the half-inch I wish I could forget.”

Her hair is so dark an auburn that it appears almost black. Her eyes are velvety brown and her skin is a creamy, gardenia tone. She’s quick in her movements and seldom still. On stage, her happy vivacity can mesmerize an audience into motionless, intense attention. Off stage, it can have its handicaps.

The aforementioned dressmaker, Miss Fanny Britman, who, with her partner, Emily Burk, creates thousand-dollar gowns for some of the world’s best-dressed women and top entertainment stars, sighs, “That Connie, she dances all the time. She can’t stand quiet two minutes. Never yet have I hung a skirt right for her.”

Then Miss Fanny beams. “But how we love to make clothes for her. Connie runs into the workroom and has coffee with our girls. And she never fails to thank them when she leaves. It’s like she carries Spring with her.”

Connie, always a deeply cherished child, was not much more than an infant when her parents sensed that she might be headed for stardom. Her father says, “We never pushed her into anything. We just tried to open doors. We knew Connie had to make music if she was to be happy.”

To make music is a family characteristic. All four of her grandparents came from Italy, and for the Franconeros and Ferreras, music is as necessary as bread. One uncle is an amateur song writer. Another uncle, Gus Ferrera, was Connie’s first and most enthusiastic fan. Her father customarily played the concertina every night after dinner. Tiny Connie appropriated it, with the result that she began taking accordian lessons before she was four years old. Her first stage was the ward of a veterans’ hospital. A local TV station was the next.

Her admiring Uncle Gus wrote a letter which put her on one of Arthur Godfrey’s shows. Her father, not to be outdone, went to see George Scheck, then producer of “Star Time,” an early network TV show featuring juvenile talent.

Scheck, who is now Connie’s manager, and her father both take delight in telling the story of how they literally bumped into each other at the door of Scheck’s Broadway office.

Scheck had been beleaguered by parents. Without introduction, he said, “So you’ve got a daughter who sings. Sorry, I’ve got too many little girl singers.”

George Franconero bristled. “But my daughter plays the accordian also.”

Said Scheck, delighted, “She does! Come on in.”

From then on. Connie was featured in “Star Time.” When finally it went off the air, she was 17 years old and associate producer. She also acted in many TV dramas. A veteran of those shows recalls, “She had unshakeable poise. At early morning rehearsals when the rest of us were too nervous even to gulp coffee, Connie would come in, happily munching a big salami sandwich, calm as you please.”

She was equally busy in Belleville High School. She edited the school paper, wrote and starred in musical shows, won a state typing contest, was valedictorian and won a scholarship to New York University. She cut her first song for MGM Records the week that she graduated from high school.

If ever a girl had a right to believe she was properly trained for immediate show business success, it was Connie.

It did not happen. That first record made a mild flurry so Connie planned for three days away from classes to do a promotional tour. Actually, she was gone three weeks. She couldn’t catch up with her skipped assignments, so she dropped out of school, all set to become a big star.

Then followed what Connie calls, “my collection of bombs.” She cut record after record. None of them sold. In the Fall of 1957, 18-year-old Connie took stock of herself and decided she was wasting her life. To her parents she announced, “I have to do something useful. I’m going to Rutgers University to study medicine.”

Her parents approved her plan, but sentimental George Franconero also liked to hear his daughter sing. Reminding Connie that no girl had got a rock ’n’ roll hit, he suggested, “Do one more song, just for me. Try an oldie, with a beat. Adults will like it and the kids can dance to it.”

He chose “Who’s Sorry Now?”. When Connie went on Dick Clark’s “American on New Year’s Day, 1958, she was ready to say she was the sorry one. Competing with the annual crop of Christmas music, the record was slow to sell. Connie says, “I thought it was another flop. I planned to go home and mail my tuition check to Rutgers.”

On January 1, 1959, she made an anniversary appearance on “Bandstand” to tell Dick Clark, “This is the show that turned the tide. Everything happened. I got a hit, night club bookings, tours, a trip to Britain, and two more gold records for ‘Stupid Cupid’ and ‘My Happiness.’ ”

Connie’s bright combination of spunk and graciousness won the hearts of the British. Following one of her first London concerts, fans and police were having a bit of a rumble at the stage door. Officers were forcibly pushing back the crowd and commanding, “Get out of here.”

Eyes flashing, Connie stepped up to the nearest bobby. “You shouldn’t treat my friends this way.”

“Go back inside, Miss. You’ll get hurt,” the officer cautioned.

“Nonsense,” said Connie. “They just want my autograph.”

Happily, she signed and chatted with the kids. When she was ready to go to her car, the crowd parted and she swept through, regal as The Queen herself. “There’s no need for a disturbance,” said Connie firmly.

Manager George Scheck and her father have carefully selected her bookings. Either her mother or her secretary, Joyce Becker, always travels with her. Even though they have all been protective, there have been adventures. Connie says, “Chicago seems to be my hoodoo. Last summer, returning from there, my plane caught fire. Then in December, when I

played the Howard Miller show in Chicago and next day went down to Springfield, I got caught in a blizzard. I had to be in Pittsburgh the next day. Planes were grounded and train schedules didn’t fit. Fortunately, Jack Scott had the same booking, so we hired a taxi to take us into Chicago. His father was with him, and Joyce was with me. Jack played his guitar and we sang all the way. Taxi fare was seventy dollars, but we had fun.”

Possibly Connie’s most serious romance to date has been with Bobby Darin. They went steady for a year—the discouraging, pre-success year. How much professional worries had to do with their breakup, neither is willing to discuss. Bobby says, “Connie and George Scheck helped me get started.”

Connie recalls, a bit wistfully, the rainy evening at the bus station when she loaned Bobby that seventy cents to go home and then had just enough money to pay her own fare. Bobby had covered his wounded pride by saying defiantly, “You’ll see, Connie. Some day we’re going to drive past here in the biggest white Cadillac that’s made and there will be a monogram ‘B&C’ on the door.”

Dreams of that joint “B&C” have ended, but Connie says fondly. “He was right about our having hits. Wasn’t it nice that ‘Splish-splash’ and ‘Who’s Sorry Now?’ went up on the charts at the same time?”

To current romance questions, Connie has a stock reply. Her eyes dance as she says, “Oh, I’m in love . . .” Then she adds, “There’s a movie actor on the West Coast, and a stage star in the East, and a singer on tour in between . . .”

At the moment, Connie wants to be in love with a different boy each week, “because right now I’m so in love with show business that I don’t want to get serious about anyone.”

The only authentic document of the state of her affections is her own diary. She has kept one for seven years. She keeps the present locked volume with her and writes in it every night.

Connie’s diary habit evoked a hit song the evening that the young composing team, Neil Sedaka and Howard Greenfield, who authored Connie’s gold record, “Stupid Cupid,” brought a group of new songs to her home.

Connie motioned them to the piano. “Go ahead and try them out. I can listen and write at the same time.”

Neil and Howie teased her, maki to see the diary. Connie was indignant. “What I write is my own secret.” The boys set it to music, Neil recorded the song himself and thereby got his own first hit record.

Connie, who hopes her future will hold movie roles and a TV show of her own, insists that she won’t marry “for years yet.” She defines her objective, “When I do, I want to be just like my grandmother. She’s a wonderful character. She was 92 on Christmas day, but she still goes on moonlight cruises and picnics with the kids because she doesn’t like old people. She had 16 children. I’ll settle for 12.”

It could be that Connie means it. She has just persuaded her father to permit her to join him in the purchase of a new ranch house in Bloomfield, New Jersey. “It’s the only argument I ever won with Dad,” she says. “All by himself, he wanted to buy a small house which would now have room enough, but which also wouldn’t be too big for mother and him when my brother and I married and moved away. I wanted to share the cost and buy a place which would continue to be our family home for years to come. It took me six months to convince him, but we got the big house. Whatever happens next, this is my home.”

THE END

BY HELEN BOLSTAD

It is a quote. SCREENLAND MAGAZINE MAY 1959

No Comments